Just about halfway between Los Angeles and Las Vegas, along a desolate stretch of Interstate 15, motorists can still see the ruins of a little-known place some believe was among the world’s first modern waterparks — a crude desert “oasis” once known as Lake Dolores.

Original owner John Byers first opened the property, which he named after his wife, to the public 1962 as a watering hole for off-road motorcyclists and tourists traveling between L.A. and Vegas. For the next two decades, Lake Dolores slowly morphed into what would be by today’s standards an unimaginably hazardous and rowdy public recreational environment.

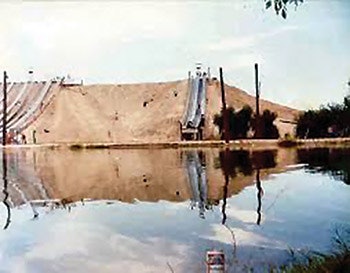

The “lake” itself was actually a 273-acre system of interconnected manmade ponds and channels, most only a few feet deep, all fed by an underground spring. The spoils from excavating the lake were used to create a massive manmade hill that towered over the otherwise dead-flat landscape.

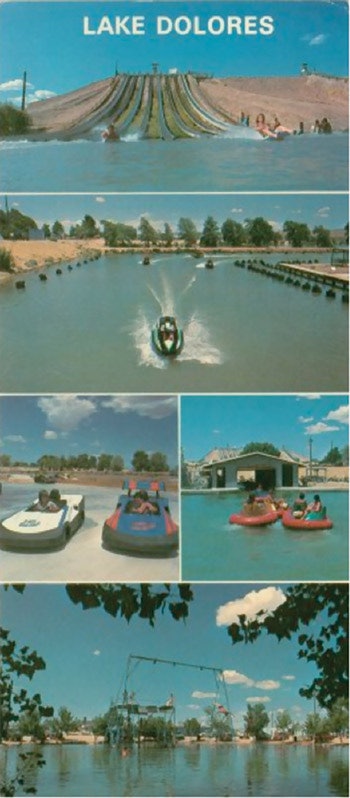

One side of the hill was devoted to eight side-by-side 150-foot long, aluminum Speed Slides. Riders plummeted head first at a terrifying 60 degrees on small inflatables over thin sheets of water. The slides flattened out at the bottom sending you skidding at a frightening pace down a narrow channel for about 50 yards.

Adjacent to the speed slides were two primitive zip lines descending from the summit at a steep angle, where you would let go and crash into the water at high speed. The challenge there was to be sure to hold on long enough to reach the water, because for the first 100 feet the lines traveled high over the gravelly slope of the hill. If you let go too early, as some did from time to time, the results were painful and often bloody.

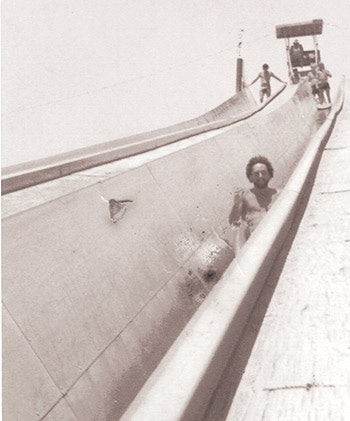

On the other end of the hill rose the park’s recreational centerpiece; a pair of features so dangerous and terrifying that no version of their species exists in modern waterpark rides today — the infamous Stand-Up Slides. As the name suggests, they were waterslides you rode standing up. The slides consisted of wedge-shaped aluminum troughs with flat bottoms upon which you attempted to stand, descending upright on a thin stream of water. Riders reached terminal velocity before being shot off the end, at a height of 15 feet with a slight downward angle toward the water waiting below.

Adding yet more probable misadventure to the fun was a 20-foot trapeze platform that rose from the center of an adjacent pond. The swings were particularly hazardous in that the inertia and centrifugal force generated by the downward trajectory made it extremely difficult to maintain your grip when reaching the arc’s nadir, typically resulting in a high-speed face plant into the water.

To their credit, the Byers were constantly adding to and upgrading the attractions, including a lazy river, bumper boats, go-cart track, a restaurant and an arcade. Eventually, however, legal and financial trouble caught up with the property; it withered and eventually quietly closed sometime in the late ’80s.

In 1990, a group of investors purchased the property, tore out the old features and installed modern waterpark slides, a restaurant and an arcade. It reopened in 1998 under the name “Rock-A-Hoola” but only lasted a short time as owners closed the park and filed for bankruptcy in 2000. Yet another group of investors tried again, reopening the park in 2002 as “Discovery Waterpark.” It operated only intermittently and again closed in 2004, leaving its structures and attractions for scrap and ruin.

Today, the ghostly remains stand as a fitting homage to a muddy legend and a by-gone age of loose restriction and physical courage.