When we talk about "design," what are we really talking about?

Naturally, the answer varies on the type of design being considered and certainly the person answering the question. Plus, there's always the "eye of beholder" principle: One person's idea of great design might to another look like an exercise in the throwing mud at a wall.

Yes, we all have different preferences and ideas about what is and isn't true creativity and, ergo, effective design. And actually, there are rules in the world of design that can be learned and applied. How to draw a perspective rendering, for example, is a discernible, attainable and, some would say, difficult skill. Working with color effectively requires an understanding of color theory, the role of primary, secondary and tertiary colors, the meaning of hue and shade or the definition of a pastel. There are rules of space, proportion, line density and perspective that can all be used to great effect.

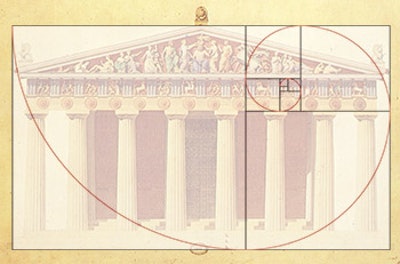

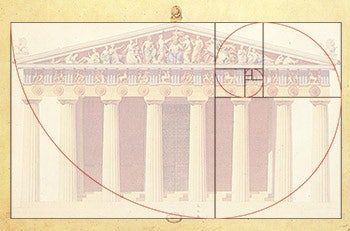

Consider, for example, the golden ratio, also known as the divine proportion, golden mean, or golden section, first described in 1835 by German mathematician Martin Ohm. In a gilded nutshell, Ohm identified a set of mathematic relationships that reoccur in nature that, among other attributes, create pleasing and harmonious aesthetics. The pyramids at Giza and the Parthenon in Athens are two commonly cited examples of structures designed using the golden ratio.

All these academic disciplines move from the abstract to the very real in the context of a specific project site. And they can play out in an infinite number of ways, but the one aspect of design that rises above all others is the experience factor. Understanding how the work we do makes people feel, how it influences what they do physically within a space and how it interacts with their daily lives cannot be understated.

My good friend and longtime industry icon Vance Gillette is fond of saying that people don't buy a Cadillac for the spark plugs, they buy it for the ride. Indeed, it's the experience of ownership, the ultimate result of design, intentional or otherwise, that dictates the way the consumer feels about our industry's wares.

In that sense, one could argue that design is really about projecting yourself into the customer's shoes and seeing through their eyes, imagining what their lives will be like after your work is done. Which is something we all do when we care about our work or even each other. In that way, we're all designers, whether we realize it or not.

Comments or thoughts on this article? Please e-mail [email protected].