Bill Goddard, owner of Goddard Construction Services, is a very busy man. When I reached him on his cell, he was watching his crew doing a dig and he told me he was heading to his office where he'd be better able to talk. "Should I call you back there." I asked. Not necessary, he said, he was just steps away from it. Bill's a guy who literally takes his office to work with him daily.

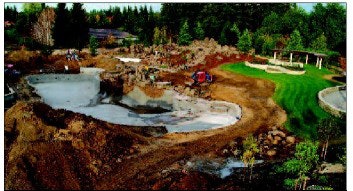

What Goddard's mobile office lacks in interior aesthetics (I'm guessing here) is made up for by its current location — on the site of a 4.2-acre estate he's helping to develop in Stockton, Calif. Like most of the projects the Woodbridge, Calif., company designs and builds, this one started as a blank canvas. The homeowners hired Goddard and, as he tells it, pretty much let him go to work. There was no bidding, little or no talk of a budget. His plan, while staggeringly elaborate, was really quite simple. "I wanted it to look like it's all been there for a million years," he says. Easy.

PLAN AND EXECUTION

The project, which should be completed by the time AQUA hits your mailbox, includes a 6,000-squarefoot, gunite-shelled swimming pond (more-accurately described as a lake) that's fed by a 125-foot-long, real-rock waterfall that gushes an astonishing 2,000 gallons of water per minute. There are also two streams, four pools, two koi ponds, a water garden, three bridges, 18 springs, a grotto, a firepit. You get the idea. Oh, and it's got a fog machine, as well.

Obviously, few designers and builders — even high-end ones — will ever be commissioned to work on a project like this one. Goddard's designing and building process, however, can be imitated on a smaller scale. In fact, he's got several tips that might help you on your next project, large or small.

HIDING THE WATER SOURCE

"When we design we really look for view angles that truly make sense," he says of the project's massive waterfall. "One of the things that I don't like with a lot of water features is they just look like they're thrown into a corner. But when we design one we want your mind to tell you that it's real."

To do that, Goddard uses oversized lines to slow the water down so that it .ows naturally over the edge of the fall.

"Rather than just having something bubbling up in the back, we made the main pond very deep and used some pinnacle rocks to kind of hide it," he says. "We tried to control the water and not let it bubble to conceal where the water is coming from. And we really dress our edges to make it look as real as it can while still making sure it functions as it should."

The rocks that make up the waterfall — all 700 tons of them — were as big as the company's heavy equipment could manage, he says.

"A good tip for some of the smaller guys is to use as big of rocks as you possibly can," he says. "That way you avoid the 'stacked look.'"

INSPIRATION

Before Goddard even starts on a project, though, he likes to get out and see what nature does. After all, that's the look he's going for.

"One thing that I do is I walk streams," he explains. "I'm not reinventing the wheel, you know. I'm just trying to do what nature's done So I get out there and see what water does when you put a rock in a certain place."

Though Goddard strives to build water features that look as natural as the streams he strolls by, it's the parts that aren't visible that can be the most important. Failure to understand that, he says, is what gets some pond builders into trouble.

"There are a lot of people who get in and out of the water feature business because they under-build them," he says. "They get pressure on price and they don't have enough margin to go back and fix a leak. So we overbuild. Most of our stuff is out of concrete, and we always have liner underneath. We put stainless-steel mesh down, we put the liner down, and then reinforced concrete on top of that. And then we put the rock on top of that. Concrete is going to crack and water will find its way to leak out, so that's why we do the liner. Now when we dig 3 to 7-acre lakes, that's all claylined stuff. But on these smaller ones we're always concrete."

Even if you don't "over-engineer" to the extent that Goddard does — and chances are you don't — you should at least take steps to protect a pond's liner during construction.

"We use a non-woven fabric and sand to protect our liner during construction," Goddard says. "And we always put down wire mesh to keep the gophers and moles from eating through the liner. We've actually had gophers and moles chew right through irrigation pipes, and if they can go through a pipe, they can go through a liner."

Steps like these add cost to a project, of course, but Goddard again stresses the importance of a good infrastructure.

"Yeah, it's underground and underwater and you can't see it, so you think you can cut this out and that out," he says. "But that will get you into trouble." Instead, he suggests, consider scaling back a visible part of the project.

PARTNERSHIPS ARE IMPORTANT

Goddard Construction Services is involved in every step of the design/build process — from the first client consultation on a featureless parcel of land to the last shovelfuls of dirt around the final plantings. That doesn't mean they don't get a little help from their friends, though.

"I lean on our suppliers for help with the filtering equipment," Goddard says. "We've got a real close relationship with them. A lot of people talk about partnerships, but we have true partnerships and we really need their expertise.

"They come out and size the systems. All of the water features are separate units and they have a combination of mechanical, biological and UV filtration and water treatment. We do all the hydraulics ourselves, but when it comes to filtration, they're a big help."

Another partnership that's important is the one between Goddard and the nurseries he works with.

"We do everything, from the ground up," he says. "And I think anybody that does high-end ponds is going to be able to plant it. But partnering with the nurseries for the selection of plants helps us come up with something that looks natural."

As for the 6,000-square-foot body of water where all that rushing water eventually winds up, Goddard says he and his crew are under strict orders to refer to it as a lake.

"The owner won't let us call it a pool," he explains. "She says, 'Bill, it's big enough to be a lake, isn't it.' And I said, 'Linda, if you want it to be a lake, it's a lake.'"