The Getty Villa stands as one of the most fascinating and inspiring art museums found anywhere in North America. Overlooking the Pacific Ocean on 64 acres of coastal hillside in Malibu, Calif., the site houses the world's largest private collection of Greek, Roman and Etruscan artifacts, all presented in a setting that boldly echoes the ancient provenance of its priceless contents.

The brainchild of oil tycoon and voracious art collector J. Paul Getty, the villa's design was inspired by the Villa at Papyri in southern Italy in the Roman town of Herculaneum, one of the cities covered by the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 A.D.

The villa opened in 1974 after 15 years of planning and construction. Sadly Getty himself, who died in 1976, never saw the completed facility. For 23 years, the property welcomed visitors from the world over who came to wander its expansive galleries and exquisite grounds. Over time, however, it became badly undersized and outdated as the Getty Foundation expanded its collections and research programs.

The villa was closed in 1997, right about the same time the Getty Center, a massive work of contemporary architecture designed to replace the aging villa, was opened 12 miles to the southeast. Hidden from public view for nine years, the villa slipped from the collective consciousness of the art world and the surrounding community.

A Hidden Reinvention

Fortunately, the Getty family and its foundation didn't give up on the site. Renowned architects Rodolpho Muchado and Jorge Silvetti were quietly selected to redesign the facility, a massive undertaking that not only included completely reworking the villa itself, but re-imagining the grounds with expanded garden areas an outdoor amphitheater, new visitor's center, expanded research facilities and headquarter offices for the foundation.

The resulting transformation was in many ways a masterwork of reinvention with countless details that enhanced and expanded Getty's original concept. Yet in some respects, some have suggested, certain elements used were highly questionable, if not truly misguided. I'll briefly discuss the misgivings below, but make no mistake, any negative critique must be considered in context with all the many things about the renovation that came off in truly spectacular fashion.

In terms of its function as a museum, the villa originally contained works from a broad spectrum of art history, but now only presents exhibits of ancient art objects drawn from a collection that includes more than 44,000 pieces. By focusing strictly on antiquities, there's now a tight harmony between the site's design and its collection, something that was missing in its previous incarnation when it also housed works of the Renaissance.

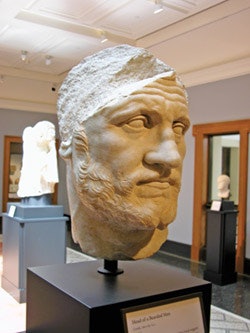

Inside the 105,000-square-foot building, once boxy and moody galleries are now open and airy, with natural light washing many of the ancient works in ever-shifting patterns of light and shadow. Its seemingly endless expanses of marble and tile mosaics were expanded, upgraded and restored and the entire floor plan revamped with display areas featuring the state of the art in lighting, climate control and security.

The site reopened in 2006 to mostly rave reviews. It's 450-seat outdoor amphitheater, peristyles, exterior frescos, vast gardens and collection of exquisite water features, all conspire to create an unfolding experience of artistic expression and timeless tranquility.

The water features serve as a study in classic aquatic design. The centerpiece is a 220-foot classically styled pool located in the main outer peristyle garden. Replicas of mythical statuary are scattered in and around the water, all surrounded by a flowering garden exploding with color and fragrance. There's a small inner peristyle garden in the main building's atrium area, featuring a smaller, yet similar shallow rectilinear pool used to display busts of historic and mythical figures. Scattered throughout the grounds are several smaller sculptural fountains, each with its own theme, along with one strikingly contemporary water wall and reflecting ponds adjacent to one of the facility's exterior stairwells.

It's a place you can visit over and over, and always find something new to enjoy.

As a side note, I'm proud to share that one of my good friends and long-time associates, landscape architect Mathew Randolph, was responsible for designing and installing large portions of the site's intricate plantings.

Designing For Designers

As a landscape architect, I work to understand the mindset of most design professionals when it comes to how they believe the general public will perceive their work. Even very early in our educational process many in my field typically design for other designers and as a result sometimes the message or intention of a space is lost in translation. Frankly, most people rarely absorb the intricate messages that designers attempt to communicate. The Getty Villa provides an example of such a situation.

The problems start with what is actually a fairly ingenious idea. Part of the program was to make the experience of visiting the villa seem as though you're visiting an archeological excavation. When you leave the parking structure and enter the grounds, you first follow a long pedestrian path that skirts a ridge just above the villa's roof. As you make your way into the property, your anticipation grows as the main building and adjacent amphitheater gradually come into view, all in a magnificent example of choreographed design. The impression of entering the archeological dig is represented with very obscure and sometimes abstract methods. As a result most visitors only fully understand this design intent after it is verbally explained to them. I find the space beautiful but, more than likely, misunderstood by most.

Another uneasy aspect of the Villa is that the designers elected to go with contemporary motifs for much of the entry areas and structures immediately surrounding the main villa building and gardens, starting with the pathway. In particular, they turned to an inventive yet discordant gimmick of using layered hardscape treatments – wood, textured concrete, stone and metal finishes – to cover many of the retaining walls and other vertical surfaces as a way to provide visual cues to the topographical orientation as you move through the site. It's a decidedly contemporary, almost sculptural architectural treatment that is almost brutally juxtaposed to the lyrical classicism of the villa itself. The visitor center, restaurant and surrounding terraces were designed in a similar contemporary modality that feels massively out of place and disruptive.

My view is simply that with such dramatic interpretation of the past on display within the villa, its galleries and garden spaces, it may have made more sense to stay with classic modalities throughout the entire site. Some may find the stark contrast interesting or somehow informative, to my eyes it forces you to tune out the contemporary elements in order to fully appreciate the essence of the villa's grandeur, although it does annunciate the transition into the historical aspect of the villa itself.

Such critique aside, the transformation of the Getty Villa stands as a magnificent example of the power of renewal executed at the highest possible level with the greatest of artistic intention. It's a place where the majesty and mystery of the past conspire with the ingenuity of the present to create a venue where future generations will be inspired to invent and reinvent their finest artistic ideas.