In the beginning, there was water.

And while it’s integral to our existence, we’ve also come to realize it feels pretty good when warm. So good, in fact, that an entire profession emerged to provide everyone the benefits of hot water.

But we all know it’s more than that. To look at a hot tub now is to look at the sum of decades worth of invention and innovation, a history of problem solving and change.

To honor that entrepreneurial spirit, we’re taking a look back at the history of hot tubs. While it’s not comprehensive by any means, it hopefully serves as a friendly reminder that the industry, at such a young age, has accomplished so much.

And the exciting thing? Who knows where it’ll go next.

1950s

Five of the Jacuzzi brothers gather around a series of industrial injector pumps

Five of the Jacuzzi brothers gather around a series of industrial injector pumps• In California vineyards, wine aficionados fill old wine vats, tanks and barrels with hot water to create the earliest hot tubs in American history. Those who were especially cunning took advantage of hot springs to enhance the experience.

1956

• Two guys wonder if they can harness the power of water to help alleviate a family member’s arthritis, and that’s how the hydrotherapy pump was born. When it proves successful, they peddle the invention to hospitals and schools. By the way, the last name of those two gentlemen? Jacuzzi.

1960s

• A new craze begins to take hold in residential design: the addition of a small body of hot water positioned next to a swimming pool. While these small bodies of water — which had just one jet at the time — delighted homeowners, they are seen strictly as accessories to a swimming pool. It will take time before we start to see standalone spas.

• The Jacuzzi brothers’ hydrotherapy pump is featured as a common prize on game shows, thus bringing hydrotherapy awareness to a national audience.

• At the same time the upper-class begin enjoying their gunite spas, the first wooden spas hit the California hills. Inspired by the traditional Japanese bathing tubs, they are typically made with materials from wineries. The wooden tubs appeal to a different audience than their gunite counterparts: the classic flower child of the ’60s.

1968

• Roy Jacuzzi invents the first self-contained whirlpool bath. It has 50/50 air-to-water ratio jets and fully-integrated plumbing. In honor of the ancient society known for its bathhouses, Jacuzzi names his model the “Roman.”

1970

• After the success of his whirlpool bath, Roy Jacuzzi tries something new. He attaches a pump, motor, heaters and filtration system to a self-contained vessel and creates a prototype of the modern portable spa.

1970s

• Around this time, a product and industry are born. Gunite spas in particular surge in popularity, but getting one is a hassle. The installation of a gunite spa requires an assembly line of different craftsmen handling different aspects of installation. It’s common for the process to take two weeks or more.

• Len Gordon, a Southern California contractor frustrated by the slow pace of spa production, seeks a faster way to meet demand. He manufactures the first fiberglass spa — a mold coated with a non-stick separating agent, gel coat and then fiberglass for strength.

• One inconvenience of early hot tubs: the electrical system. Switches and controls were located a short walk from the tub, a problem everyone tried to solve. Gordon creates a simple solution: an air switch.

• Throughout the decade, wooden hot tubs dominate the spa market. They are low-cost and better known than fiberglass or acrylic — yet the other segments were beginning to grow.

1973

• Baja Products begins producing acrylic spas, which eventually become the champion of the industry.

1974

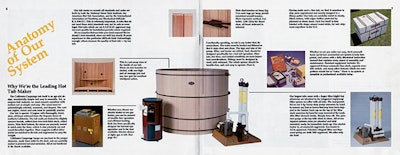

• The largest and best known of the wooden tub makers, California Cooperage, begins operations.

1976

• Baker Hydro creates the spa pack for HydroSpa. An integrated unit fitting under the skirt, it helps streamline the industry’s approach to plumbing.

1979

• Fiberglass spas grow popular among customers, and everyone wants a piece of the pie. People begin setting up shops in garages to whip out copies of fiberglass spas — oftentimes doing so by borrowing a hot tub, making a mold from it and using the mold to make new copies. The practice, called “splashing,” is deemed illegal.

• As both reputable and sketchy spa manufacturers flourish, so, too, do complaints and skepticism toward the industry. Problems with poorly-made fiberglass spas plague the industry and force some manufacturers to close — yet this opens the way for acrylic spas to join the party.

Early ’80s

• As other manufacturers begin to see problems with surfacing — blistering, splintering and more — the Watkins brothers release a spa made of Rovel, a co-extruded material from Dow. An innovation from the boating industry, the material uses vinyl ester resin and acrylic instead of polyester resin, swiftly resolving surface problems.

• The wooden spa begins its decline in favor of portable spas.

Mid-80s

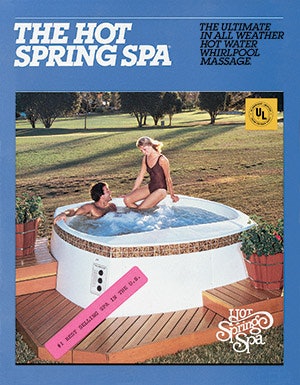

• Thanks to their convenience and ease of installation, portable spas begin surging in popularity and soon take the sales lead over ingrounds.

• Basic controllers begin to appear on hot tub to help manage the various features. More and more, the portable spa begins to resemble what we see today.

1988

• Spa sales reach a record 280,000.

The ’90s

• Product turns a corner in reliability and quality. “In the ’80s, consumers hoped the product would work, and in the ’90s, they expected the product would work,” says Stan Chambers, AQUA’s West Coast account executive and 30-year industry veteran.

• While the spa industry has largely been a product of California, it grows to a national level in the ’80s and goes international in the ’90s.

1995

• Hot Spring debuts the synthetic cabinet. As the cost of redwood increases due to scarcity, this development helps cut manufacturer costs, but it also makes hot tub ownership easier and more convenient for customers.

Mid-90s

• The industry continues to mature as smaller manufacturers disappear, leaving a core group to grow and dominate the market.

• The retailer landscape changes, too. Smaller retailers looking to cash in on the hot tub craze fade away, leaving top professional outfits to prosper in local markets — most of whom are still around today.

• Cooperative advertising programs between dealers and manufacturers flourish.

• Portable spas become much more sophisticated and elaborate. “I remember the ’90s as an era of what I’ll call ‘more for more.’ There was a significant feature proliferation on products,” says Mike Dunn, executive vice president at Wakins. More color options became available, more jets were added and horsepower increased. And as these features were added, hot tub prices increased accordingly, Dunn says.

• New marketing themes emerge. “Back in the ’70s and ’80s, the hot tub was more about relaxation and fun and partying. As we went into the ’90s, there was a much greater focus on the hydrotherapy benefits of the product,” says Jeff Kurth, president and CEO of Wexco, the parent company of Marquis Spas and Fox Pool Corporation. Manufacturers add more jets to target specific areas of the body and promote the improved health and wellness hot tubs could provide.

2000s

• The green movement takes hold in the hot tub industry as manufacturers produce tubs that are more energy efficient.

• Product complexity, especially at the high end of the market, increases dramatically. “The rate of change increased significantly,” Kurth says. “The number of jets, the stereos, the iPod docks, Wi-Fi, flat-screen televisions, lighting systems — the product is so much more complicated and sophisticated today.” Dunn describes these add-ons as “experiential, entertainment” features designed to meet the needs of a visual customer base. “We would have used the phrase ‘they buy with their eyes’ to describe them,” he says.

2007

• With very little warning, the American economy plunges into a deep and sustained recession. As home valuations dive, home equity financing of hot tubs dries up. Faced with great economic uncertainty, the core market for portable spas — the American middle and upper middle class — reigns in spending. Hot tub retailers and manufacturers are hit hard, while hot tub service remains relatively strong as many owners continue to maintain their units.

Present

• As customer confidence begins to rebound, the sales message in the hot tub industry changes. “Before, you had to talk ‘value, value, value.’ Now it’s, ‘You can have what you want.’ The whole language of selling is much more sunny,” says Alice Cunningham, co-owner of Olympic Hot Tub Company in Washington.

• Hot tub controls can now be controlled through computers and smartphones.

• Water care has advanced with new technologies like ozone and saltwater systems. “All are aimed at trying to make the ownership experience for a consumer easier,” Dunn says.

What’s next?

Kurth expects the industry will experience slow growth in the coming years, but he also sees one way to gain momentum.

“I think we as an industry have to do a lot more to make the hot tub relevant and top of mind,” he says. “Over the last several years, as the industry has taken such a downturn, there’s not a lot of advertising dollars being put into the national media.”

Cunningham agrees, and cites the boating and RV industries as models to follow.

“They came together and did these massive campaigns, not about a particular manufacturer, but about the joys of boating, the joys of RV-ing. Hot tubs and spas are in the same category, but the industry has never been able to mount a successful campaign to get into the consumers’ minds,” Cunningham says.

Yet looking at today’s hot tub, one thing is certain: “The products have never been better. They’ve never been more reliable or efficient,” Cunningham says.

Comments or thoughts on this article? Please e-mail [email protected].