Over two hundred years ago, a new word was coined: panorama. Today, a panoramic view can be created relatively quickly with nothing more than a smartphone by simply selecting the appropriate camera option and moving the lens in the desired direction. When Robert Barker, the landscape painter who created the first panorama, wanted to share a sweeping, 360-degree view of the beautiful scenery he saw in Scotland, however, he had no such tools at his disposal.

To capture the full splendor of Edinburgh as he saw it from Calton Hill, Barker wanted to do far more than simply recreate what he saw on a typical canvas. Instead, he set a more ambitious goal: “to perfect an entire view of any country or situation, as it appears to an observer turning quite round” so that “the observers [would]…feel as if really on the very spot.”[1]

That would be a matter of clicks today, but in the 18th century, how could such an enormous and compelling effect, with the ideal scale and perspective, be created?

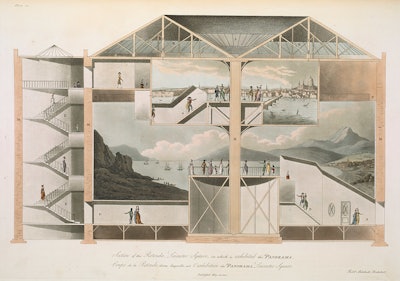

For Barker, even the most expertly executed painting would not be enough to fully capture what he wanted to share. Before he could invite people to see what he envisioned, Barker had to imagine and build an entirely new space that would immerse his viewers in every detail — a necessity given the sheer size of his creations, with one depiction measuring in at nearly 1,500 sq. ft.[2]

In 1787, he patented his resulting invention, which he initially called “La nature à coup d’œil,” or “Nature at a glance.” Every detail was expertly planned so as not to disrupt the illusion and make it seem that the viewer had literally walked out onto a platform with an astonishing 360-degree view.

He lit the scene from above, paying close attention to the falling “lights and shadows” and carefully arranged the entrance from below, choosing the right “interception” at the bottom to make certain “nothing could be seen…but the drawing.”

His efforts proved successful — so much so, in fact, that a contemporary poet would compare his invention to a mirror. As fascinated as viewers were by his take on the view of Edinburgh that initially inspired him, when he took his invention to the biggest city in Europe, it created an immediate sensation. His panorama of London was a hit, as he presented locals and tourists alike with a remarkable new way to see the city where they already were.

In seeking a better way to share scenic views that he enjoyed, Barker invented a way to create immersive experiences that many people would not just enjoy but also willingly pay to enjoy. That impulse — to create something that is not merely attractive to look at but also a spectacularly immersive experience — is also the foundation of the pool industry. It’s what builders do.

The power of that experience is not just subjective speculation, it has been scientifically demonstrated by Amit Kumar, a researcher who has shown that doing makes us notably happier than merely having. In fact, Kumar and his colleagues have found that the significant difference between enjoying an experience versus enjoying a possession extends even to how enjoyable it is to look forward to that experience.[6]

That distinction is echoed by advice given by marketing executive Rory Sutherland: “We don’t value things; we value their meaning.”[7] Barker’s invention proves the truth of that assessment, for in it he took care to plan details down to the ventilation in order to make certain that what he was creating would achieve the “proper effect.” It was not the proposed glazed dome or carefully planned entrance that Barker expected to impress visitors to his panorama but instead the thoroughly planned experience, one in which even “the inner enclosure may be elevated, at the will of an artist, so as to make observers, on whatever situation he may wish they should imagine themselves, feel as if really on the very spot.”

Barker’s creative impulse and genius is echoed today in the works of top pool builders all over the world, and their works inspire for exactly the same reasons.

As Barker understood, the technology backing his invention was inseparable from the artistry. Just as today’s clients would not likely be inspired to build a pool based on nothing more than the technical specifications of the plumbing required for it, Barker could no more entice viewers to an unadorned rotunda than he could show them all 1,500 sq. ft. of his painting without well-planned structural support. Experiencing one meant experiencing the other, with the viewer’s anticipation rising as they ascended the stairs.

When facing the decision to build a pool, update the landscaping, or even undertake a full renovation of an outdoor living space, one challenging obstacle in the decision-making process that prospective clients might face is, surprisingly, an obstacle that many designers and builders sometimes overlook: making certain that clients fully understand what it is that they are seeing when they look at your design. As renowned management expert Peter Drucker has made clear, a vital step in making any decision is being certain you clearly understand the goal[8]; his advice is as relevant to clients as it is to designers. To make the decision to buy, a client needs to be able to fully understand the meaning and the value of the options being offered to them.

To the experienced eye, design plans are effortlessly easy to understand. Clients with little practice interpreting such plans, however, might struggle to “read” them as much as they would if asked to envision their completed house solely from the architect’s blueprints. In an 1806 advertisement, Barker’s son demonstrated his answer to this problem: He drew a detailed key to the panorama on display. Not only does the shape of his drawing match the shape of the two panoramas on display, giving prospective visitors a preview of what they would soon see, it also serves as a reassuring guide — pointing out notable landmarks, providing a sense of direction, and letting visitors know “a person always attends to explain the painting.” Then, it invites visitors to participate: “now form a judgment of the comparative excellence of three views.”

As the success of Barker’s strategy suggests, taking as much care with the experience being shared as with the design being planned can prove remarkably compelling. By focusing on creating a meaningfully immersive experience that helps to build an emotional connection, it’s possible to help clients make decisions that lead to far more, and far longer-lasting, satisfaction with their pool purchase.

Noah Nehlich, author of Design for Story: Create Immersive Outdoor Living Experiences, is the founder of 3D design software company Structure Studios. For the past two decades, Noah has helped thousands of designers, builders, and salespeople leverage 3D design tools to amaze their clients and achieve their business goals by teaching that great designs offer far more than concrete and water: They create an emotional connection. His goal is to improve lives through 3D experiences.

[1] Barker, Robert. Patent for Displaying Views of Nature (1787), The Repertory of Arts and Manufactures, London, 1796

[2] “A Key to the Panorama of London from Albion Mills.” Graphic Arts Collection. Special Collections, Firestone Library, Princeton University. https://graphicarts.princeton.edu/2019/02/05/a-key-to-the-panorama-of-london-from-albion-mills/

[3] William Wordsworth, The Prelude, Book 7, lines 232-234

[4] Ivan Sutherland, “The Ultimate Display,” Proceedings of IFIP 65, vol 2 (1965): 506–508

[5] See “panorama, n.”. OED Online. September 2021. Oxford University Press. https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/136923

[6] Kumar, Amit, Matthew A. Killingsworth, and Thomas Gilovich. “Waiting for Merlot: Anticipatory Consumption of Experiential and Material Purchases.” Psychological Science 25, no. 10 (October 2014): 1924–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614546556; emphasis in the text

[7] Rory Sutherland, Alchemy, Custom House: Kindle Edition,s 136

[8] Drucker, Peter F. “The Effective Decision.” Harvard Business Review (January 1967)

[9] Barker, Henry Aston. “A View of Edinburgh. An advertisement for Robert Barker’s Panorama exhibited at Leicester Square.” Engraving in paper. 1806. https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-andartists/63244/view-edinburgh-advertisementrobert-barkers-panorama-exhibited-leicestersquare