The following content is supported by one of our advertising partners. To learn more about sponsored content, click here.

During the pandemic, Americans added more hot tubs to their homes than at any time in recent history. Last year, more than 70% of dealers reported another sizable jump in sales, even despite difficulties filling orders.

People love their hot tubs, but there’s reason for concern. The majority of new hot tub owners are either sanitizing their hot tubs incorrectly, right from the start, or struggling to keep their water clean, clear, balanced and sanitized. Research shows that more than 60% of hot tub owners are using methods better suited to sanitizing pools than hot tubs, adding chemicals that ultimately create more problems than they solve, resulting in cloudy or bad-smelling water, proliferation of harmful bacteria and microorganisms, and causing hot tub owners untold headaches and extra maintenance.

The surprising part? Most of these hot tub owners are following the recommendations of their dealers; they look to you for expert advice and help.

Source Robert W. Lowry

Source Robert W. Lowry

It's Time To Stop Recommending — And Using — Dichlor.

Dichlor is short for sodium dichloro isocyanurate. It’s the form of chlorine most commonly used (or rather, mis-used) in hot tubs. The problem is not with the chlorine, but with cyanuric acid — it makes up approximately half of dichlor’s content. Cyanuric acid, CYA, has been a huge boon to pool disinfecting, because it significantly slows the breakdown of chlorine in sunlight. But in hot tubs, where UV rays are not a factor, CYA can build up quickly — with frustrating, and potentially dangerous, consequences.

Why? Because chlorine — the hard-working sanitizer in dichlor — binds to the CYA in hot tub water, making an increasingly smaller portion of it available for disinfecting. Ultimately, CYA impairs chlorine’s ability to kill the bacteria and microorganisms that lead to cloudy or smelly water, and worse.

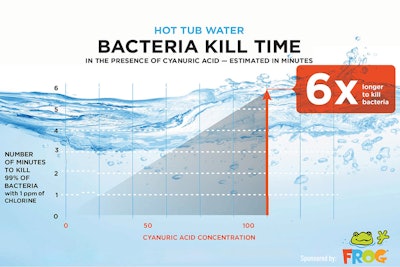

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the microorganism that is responsible for the condition known as “hot tub rash” and in rare cases, urinary tract infections. While chlorine alone will kill it in about 20 seconds, once cyanuric acid has been introduced into the hot tub — even at just 50 parts per million — it can take chlorine four or five times longer to do its job. The more dichlor (and resulting CYA) is present in the water, the more chlorine is bound up, and the less of it is available for disinfecting. When CYA is at 100 parts per million (still a relatively low amount) the kill time for pseudomonas aeruginosa is nearly two minutes. And it goes up from there.

The CDC: Chlorine With CYA in Hot Tubs Is a No-No.

CYA buildup and the increase in microorganism kill times has led the CDC to issue this warning: “The CDC recommends NOT using cyanuric acid or chlorine products with cyanuric acid in hot tubs and spas.”1

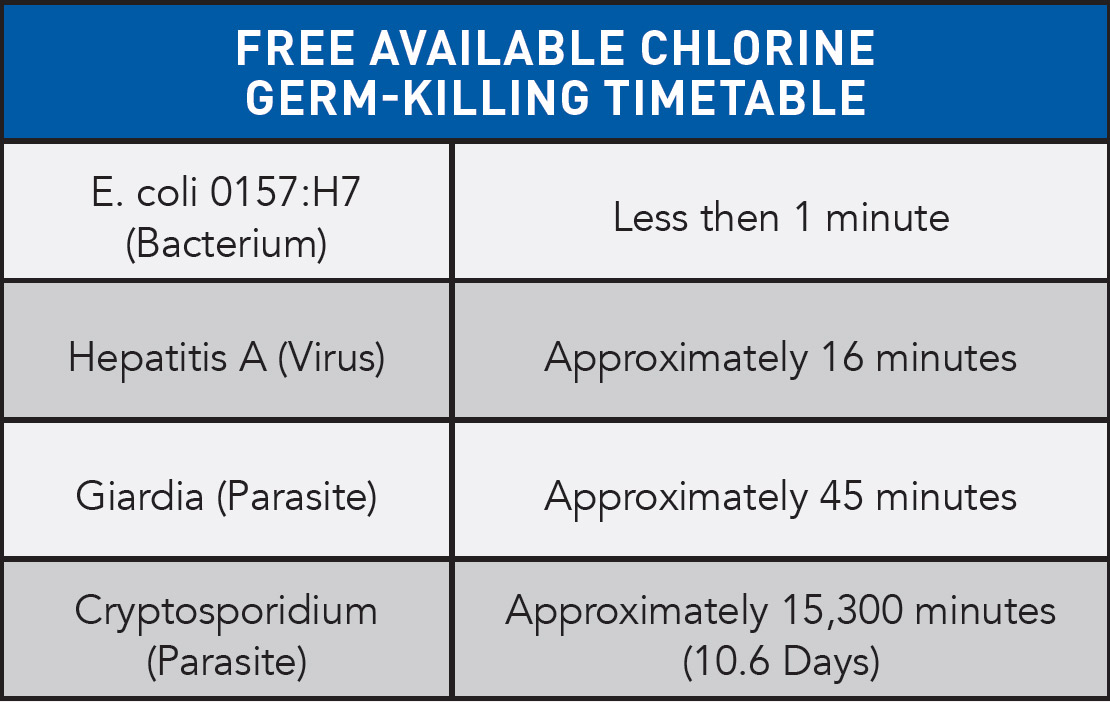

In the article “Water Treatment and Testing,” the CDC continues: “Free chlorine kills most bacteria, such as E. coli, in less than a minute if its concentration and pH are maintained as CDC recommends. However, a few germs are moderately (Giardia, Hepatitis A) to very (Cryptosporidium) chlorine tolerant. The table below shows the approximate times it takes for free chlorine to kill these germs.”

Notes: Ties based on 1 ppm free chlorine at pH 7.5 and 77 degrees Fahrenheit (25 degrees Celsius). These disinfection times are only for pools and hot tubs/spas that do not use cyanuric acid. Disinfection times are longer in the presence of cyanuric acid.

Notes: Ties based on 1 ppm free chlorine at pH 7.5 and 77 degrees Fahrenheit (25 degrees Celsius). These disinfection times are only for pools and hot tubs/spas that do not use cyanuric acid. Disinfection times are longer in the presence of cyanuric acid.

The Pennsylvania Dept of Health spells it out even more clearly stating, “Cyanuric acid can cause adverse human health effects and can eliminate chlorine’s effectiveness against Cryptosporidia,” which is extremely chlorine tolerant.2

More CYA Requires More Chlorine. The Perfect Catch 22.

As cyanuric acid builds with the continued use of dichlor, more and more chlorine is required to kill microorganisms quickly and keep hot tub water clear. Each increase in CYA levels calls for a corresponding increase in free chlorine, which makes the free chlorine a moving target. Hot tub owners are concerned — and should be — about over-chlorination. As the Environmental Protection Agency, EPA, warns: “The maximum for free chlorine in hot tubs (while bathers are present) is 5.0 ppm.3 Indeed, a hot tub owner using dichlor can reach the 5.0 maximum quite quickly.

Corrosion Adds Insult to Injury.

Another negative effect of Cyanuric Acid buildup? Corroded, stained or damaged surfaces. It’s not just the acid itself that’s the problem, it’s that CYA levels affect Total Alkalinity, TA, a fact many hot tub owners are not aware of. TA is actually NOT as high as the readings appear, and because hot tub owners aren’t chemists, they fail to take that into consideration while water-balancing. The result is corrosive water: super uncomfortable to the skin, plus it leaves its unwelcome and lasting mark on surrounding surfaces.

First, Frustration. Then, Refilling.

Cloudy water, odorous water, skin irritations, stained surfaces: It’s no wonder CYA buildup causes hot tub owners to throw up their hands. To compound trouble, the most common recommendation to solve CYA buildup is a chlorine shock — essentially a mistake meant to correct a mistake. More dichlor further elevates the CYA level, and before long (often within 10 weeks or less) the water is unrecoverable. There’s nothing to be done but drain the hot tub and start over. And that’s when many hot tub owners decide the whole thing is just too much work.

The CYA-Free Solution.

How do you sanitize a hot tub effectively without causing a buildup of CYA and its resulting problems? By following CDC recommendations and using disinfecting products that contain no Cyanuric Acid. FROG® @ease® is one good choice. It has 0% CYA. Plus, it’s self-regulating, meaning it consistently delivers a low, but effective amount of chlorine that works in combination with minerals to kill bacteria and microorganisms (including pseudomonas aeruginosa). It’s the way to maintain clear, soft water that lasts far longer — with minimal effort. It’s the way to make a hot tub the antidote to hard work — instead of the chore.

To learn more, go to frogatease.com.

References

- https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/swimming/pdf/hyperchlorination-to-kill-crypto-when-chlorine-stabilizer-is-not-in-the-water.pdf

- https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/swimming/pdf/hyperchlorination-to-kill-crypto-when-chlorine-stabilizer-is-not-in-the-water.pdf, https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/swimming/residential/disinfection-testing.html

- https://www.health.pa.gov/topics/Documents/Programs/Operations-SOPRecommendations.pdf

Sources For This Article

- https://www.health.pa.gov/topics/Documents/Programs/Operations-SOPRecommendations.pdf

- https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/swimming/residential/disinfection-testing.html

- J.E. O’Brien, J.C. Morris & J.N. Butler, “Equilibria Aqueous Solutions of Chlorinated Isocyanurate” Ch. 14 in Alan J. Rubin’s Chemistry of Water Supply, Treatment and Distribution”, Ann Arbor Science Publishers, Inc., 1974, ISBN 0-250-40036-7, pp. 333-358

- Anderson, J.R., “A Study of the Influence of Cyanuric Acid on the Bactericidal Effectiveness of Chlorine,” American Journal of Public Health, Oct, 1965. “Your Disinfection Team: Chlorine & pH.” CDC article issued May 2016

- “Public Swimming and Bathing Places: Operational and Biological Protocol Recommendations.” Pennsylvania Department of Health in December 2016

This article first appeared in the November 2022 issue of AQUA Magazine — the top resource for retailers, builders and service pros in the pool and spa industry. Subscriptions to the print magazine are free to all industry professionals. Click here to subscribe.